#2 Our Failed Response

The Perils of Fragmentation

To quote the great systems thinking theorist, Donella Meadows:

"The destruction [systems] cause is often blamed on particular actors or events, although it is actually a consequence of system structure. Blaming, disciplining, firing, twisting policy levers harder, hoping for a more favorable sequence of driving events, tinkering at the margins – these standard responses will not fix structural problems."

We - the homeless service sector - fundamentally do not control the upstream issues causing this crisis (e.g., the cost of housing, access to behavioral health services, declining social capital).

Instead, the only thing we actually control is the nature of the response to the housing crises resulting from these issues.

And over the last 45 years, we - the homeless service sector - have fundamentally decentralized the response to homelessness in this country, largely leaving states, counties, CoCs, cities, and service providers to their own devices to figure out what to do.

In systems thinking, a feedback loop is a mechanism that creates a predictable pattern of behavior over time. The pattern might be "balancing," such as a thermostat keeping a room the same temperature. Alternatively, it could be reinforcing, such as the proverbial snowball rolling down a hill getting bigger and bigger.

The structural decentralization of our response to homelessness has produced six extremely powerful feedback loops that have made it nearly impossible to mount an effective response to this crisis.

#1 Reluctance from Local Governments

Because of insufficiently coordinated and enforced state and federal strategies for ending homelessness, the thousands of city, town, and county governments across our country are each independently responsible for addressing homelessness in their own local way.

To dramatically oversimplify, each government agency essentially has two options:

- Option A - Attempt to house and provide services for everyone who is homeless

- Option B - Do not provide housing and services and instead redirect people to other communities

There are two big reasons why local leaders do not pursue Option A:

- The cost of providing housing and services is substantial (especially without sufficient state and federal support).

- There is a pervasive and pernicious belief that most people experiencing homelessness are not "local" (i.e., they became homeless somewhere else and then moved to the community). This belief signals an assumption that other communities have already selected Option B.

If there is anywhere to examine the “local” vs. “non-local” question, it is the San Francisco Bay Area. As one of the most liberal and service-rich parts of the country, not to mention having fantastic year-round weather, the Bay Area would seemingly be a magnet for nationwide homelessness.

Seven of the nine Bay Area counties do, in fact, track the origin of people's homelessness, and these studies consistently find that at least 70%, and in some cases close to 90%, of people experiencing homelessness in the Bay Area were already living in their current county when they became homeless (this data is from local Point-in-Time Counts).

These findings have been further corroborated by long-term data from the State of California, which has shown that 96% of people experiencing homelessness throughout the state only access services in one community.

(If anything, the relatively higher rates of homelessness in Coastal California communities like the Bay Area are the result of a particularly strong concentration of the systemic forces detailed in "A Crisis We Didn't Create")

Given these statistics, I am always surprised by how certain community members are that the revolving faces they see on the street are people from other communities.

In reality, rather than people moving across communities, it is much more common to see movement within a community.

This was evidenced by an amazing, year-long story in the San Francisco Chronicle called "Seven Lives, Seven Paths, Little Change Seen."

As the City of San Francisco cracked down on unsheltered homelessness in one neighborhood, people simply shifted to a different neighborhood.

From each neighborhood’s perspective, it appeared that there were constantly new faces, but if you zoomed out even slightly, it was easy to see it was the same people moving within the same city.

Despite the data, the fear is real and must be overcome. And it is important to see that the hyper-localization of our response to homelessness makes this dynamic worse because it is not easy for civic leaders to see what is happening outside of their particular jurisdiction.

This fear has led to our first feedback loop. The default strategy in many communities is to blame local homelessness on [insert neighboring city / county]. This creates a reluctance to invest in local resources. This lack of resources results in increases in local homelessness, which increases feelings of otherness, thus perpetuating the cycle.

#2 "The Homeless Industrial Complex"

Over time, the term “[insert industry] industrial complex” has come to connote nefarious and self-serving tendencies within a given economic sector. It is:

A socioeconomic concept wherein businesses become entwined in social or political systems or institutions, creating or bolstering a profit economy from these systems. Such a complex is said to pursue its own financial interests regardless of, and often at the expense of, the best interests of society and individuals. Businesses within an industrial complex may have been created to advance a social or political goal, but mostly profit when the goal is not reached. The industrial complex may profit financially from maintaining socially detrimental or inefficient systems.

To be very clear, in all of the time I have been working to end homelessness, collaborating with hundreds if not thousands of colleagues, I have not once met a person who is “pro-homelessness.” There is no grand, corrupt conspiracy to perpetuate homelessness for the enrichment of those working in this space. Every person I have met in this field is genuine in their desire to help people and make a difference. And frankly, I think social workers and care providers should be more highly compensated, given the stress, demands, and importance of this work.

Nonetheless, it is common to hear frustrated community members claim that the people working to solve homelessness are in fact part of the “homeless industrial complex.”

While this insinuation certainly stings, in all fairness, the social service sector as an “industry” is not above reproach.

No one wants homelessness, but over time, because society has failed to take the necessary steps to prevent it from happening in the first place, a large and robust homeless service system has emerged to try to help people regain housing.

Unfortunately, as anyone who has worked in this field will know all too well, structural inefficiencies often emerge as these social service systems grow, which makes solving homelessness even harder than it already is. This is primarily driven by a lack of coordination.

- “Silos” form when departments, organizations, or agencies operate independently without sharing information or coordinating activities.

- Without coordination and data sharing, it’s impossible to effectively measure what works and what does not.

- Without a process for determining what works and what doesn’t and investing accordingly, many communities default to creating "new" programs and organizations, thus perpetuating and exacerbating the cycle (importantly, most of the time this so-called "innovation" is just rebranding or renaming existing programmatic interventions).

#3 Chronic Homelessness

It's important to recognize that the unnecessary complexity of our social service systems impacts the most vulnerable people the worst.

When people experience homelessness for long periods of time, we often make them the subject of the problem.

- "It's a choice."

- "They're service resistant."

- "They're just too sick to help."

While there are of course people who can be very hard to engage, we must recognize the ways in which our siloed and decentralized systems make it harder for people to access the help they need.

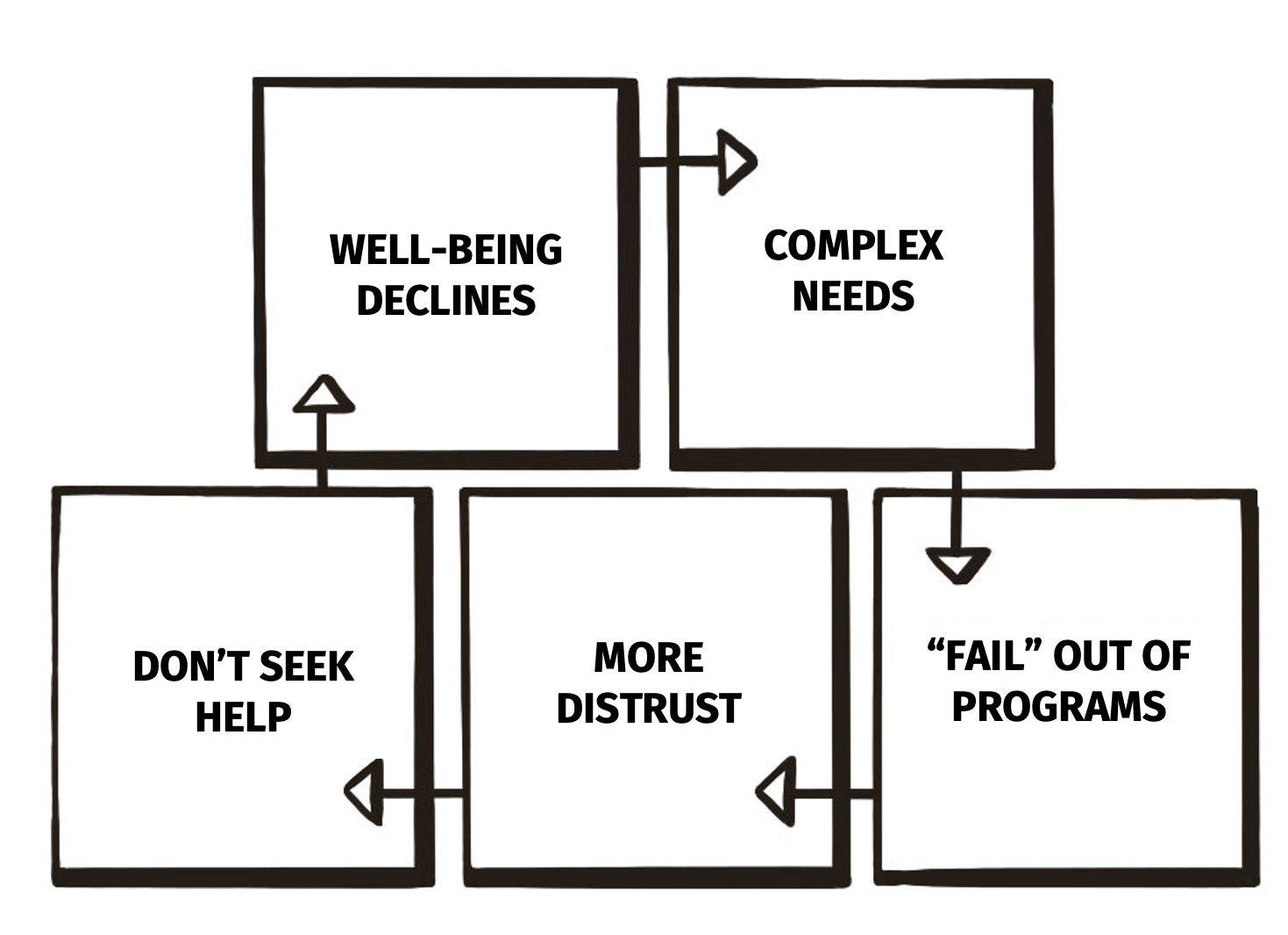

- By definition, people experiencing chronic homelessness have disabling health conditions (physical health, mental illness, addiction, traumatic brain injuries).

- When our systems are confusing to navigate or have high barriers to access, people understandably disengage and become distrustful.

- As this happens, people's underlying challenges worsen, which makes it even harder to help them later.

#4 The Leadership Tide

As our systems become more complex and disorganized, it becomes extremely difficult for any one person or organization to gain perspective on how all of the pieces actually fit together.

This is exacerbated by the fact that our movement does not have a shared story describing how we got here or a shared framework / strategy guiding our efforts moving forward.

Instead, individual human beings come into homeless systems of care with preconceived ideas and assumptions about how we should be responding.

The result, as concisely stated by Nithya Raman, Los Angeles City Councilmember and Chair of the City’s Homelessness Taskforce, is that:

"We have 15 different Council Districts and 15 different approaches to homelessness."

Unfortunately, as leaders and practitioners do gain more knowledge and understanding, the inevitable - life itself - happens. People move on to other jobs or projects. They get burned out and quit. Some simply retire.

Because of the way we have decentralized our response, this leadership turnover means we are constantly losing hard earned institutional knowledge rather than absorbing it into our broader collective strategy and efforts.

As a former colleague who used to work for the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA) once described it to me:

We are never going to solve homelessness in Los Angeles because it's like the tide. Every few years a new group of leaders washes in with "new" insights and "new" ideas. However, after a few years, after they finally ascend the learning curve to understand what really works, they wash out, a whole new group comes in, and the process starts over again.

I now refer to this phenomenon as "the leadership tide."

#5 Short-Termism

In an important way, the leadership tide actually helps to drive our first feedback loop - local government disinvestment.

Local leaders, particularly political leaders, who know they will only be working on this issue for a relatively short period of time before moving on to something else, are not incentivized to make hard, long-term investments.

Instead, these leaders are often simply trying to "do something" in response to an understandably frustrated public. Unfortunately, this type of reactive "do something" activity often takes the form of pushing encampments from one neighborhood to the next or even trying to criminalize behavior or conditions associated with experiencing homelessness.

As was the case in San Francisco, these efforts might create the illusion of a short-term win for a narrow group of constituents, but in the long-run, they take the focus away from the type of investments that will end homelessness in the first place - namely more affordable and supportive housing, a living wage, and easier access to behavioral health services.

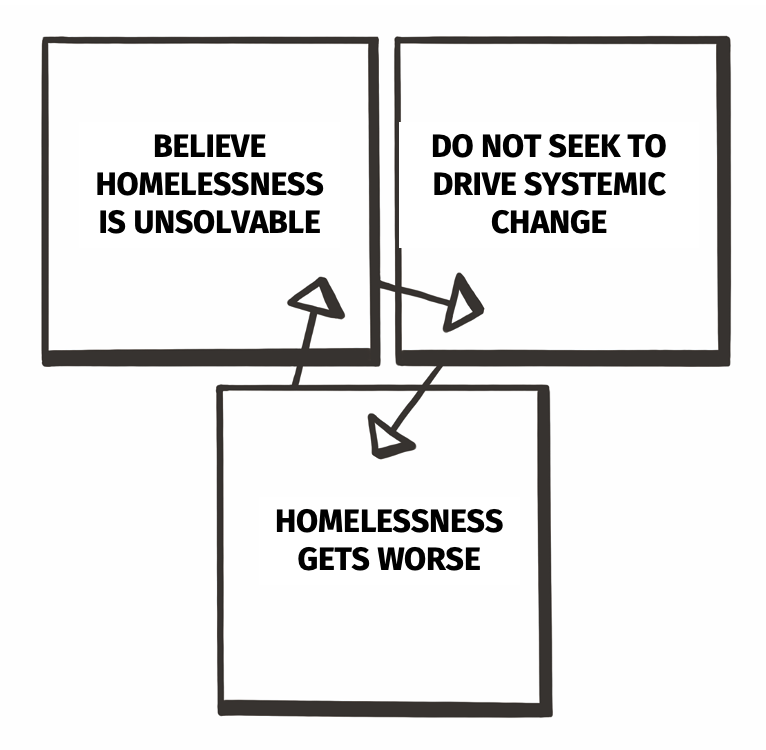

#6 Hopelessness

Given all of these dynamics, it's easy to lose hope.

As San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown famously declared in the early 2000s:

"Homelessness in unsolvable."

Homelessness is not inevitable, as evidenced by the fact that it has emerged and then disappeared many different times throughout our nation's history. However, the sad truth is that, today, our response to modern homelessness is not delivering results. And it will continue to fail to so as long as we keep:

- Decentralizing our response

- Creating unnecessarily complicated systems

- Needlessly "innovating"

- Failing to spur systemic investment or policy change that get to the root causes of this crisis

These failings almost certainly guarantee that homelessness will continue to feel unsolvable. And that feeling will keep us stuck with an inhumane, incompassionate status quo that no body wants.

If we are ever going to solve homelessness in this country, we have to start operating from a shared "north star," orienting local communities towards proven solutions.